Guesswork is expensive. That is why major manufacturers stopped doing it.

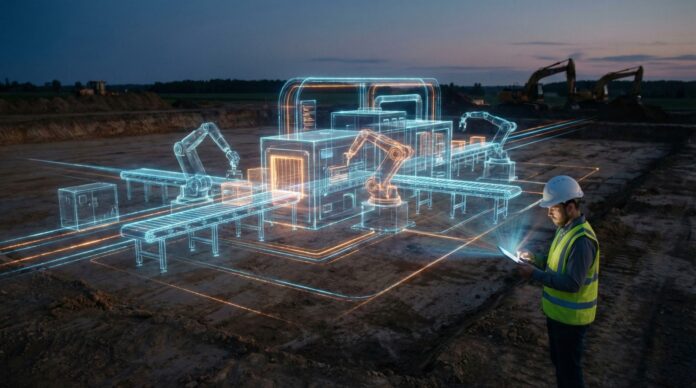

Early 2026 marked a quiet but distinct threshold for the industrial sector. For the first time, top-tier production facilities are being fully commissioned in software before a single foundation is poured. Titans like PepsiCo, Siemens, and NVIDIA aren’t just drafting blueprints; they are validating conveyor speeds and robot trajectories in physics-accurate virtual voids.

This isn’t about technological novelty. It is about money. With capital expenditure (Capex) costs for new semiconductor and consumer goods factories spiking, the old “build-then-fix” model is dead. Simulating operations now allows companies to catch 90% of integration errors during the design phase. This proactive error detection slices Capex by 10-15% and shrinks ramp-up time from months to mere weeks.

From Static Models to “Physical AI”

Forget the passive 3D CAD models of the early 2020s. The digital twins of 2026 are aggressive. They don’t just reflect current conditions; they predict them using “Physical AI.” These systems understand gravity, friction, and heat.

In these environments, AI agents act as virtual stress-testers. Engineers can now push a button to simulate a 30% surge in raw material input. The digital twin doesn’t guess; it calculates the cascading crush on storage, energy consumption, and machine wear. If a robotic arm is going to overheat, it fails on the screen—not on the factory floor. Engineers swap the component in the file, saving a fortune in physical retrofits.

The Rise of the “Digital Twin Composer”

Interoperability used to be a headache. Now, it’s the standard. In mid-2026, Siemens released its “Digital Twin Composer,” a tool fusing real-time engineering data with NVIDIA’s Omniverse. This allows disparate data types—architectural blueprints, machine sensor data, and logistics schedules—to coexist in a single, high-fidelity simulation.

This unification solves the fragmentation problem that plagued earlier iterations. Previously, the facility’s shell (architecture) and its contents (machinery) lived in incompatible software formats. Now, a change in the building’s ventilation design automatically updates the thermal cooling assumptions for the machinery below. Systems are sized correctly from day one.

Case Study: PepsiCo’s Virtual Commissioning

PepsiCo provided the blueprint for this shift. Utilizing the Siemens-NVIDIA stack, they didn’t shut down lines to test upgrades. They digitized them.

Instead of halting production, PepsiCo ran thousands of simulations in the digital twin. They modeled pallet routes, operator foot traffic, and machine interaction speeds. The software flagged bottlenecks that would have choked throughput in the real world. By fixing these digitally, they achieved a 20% increase in throughput the moment the physical “on” switch was flipped. This is “virtual commissioning”—ensuring the factory works before it exists.

Data Analysis: Traditional vs. Digital Twin Construction

The numbers illustrate the efficiency gap between legacy construction and the 2026 approach.

| Metric | Traditional Build Approach | Digital Twin-First (2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Error Detection | During construction or post-launch | 90% identified during design phase |

| Commissioning Time | 3–6 months of physical calibration | 2–4 weeks (pre-calibrated virtually) |

| Capital Expenditure | High (includes budget for rework) | 10–15% Reduction (minimal rework) |

| Flexibility | Rigid; changes are costly orders | High; iterate designs at zero cost |

| Throughput Optimization | Reactive (tweaked after launch) | Proactive (optimized pre-launch) |

Edge Computing and Autonomous Operations

The simulation doesn’t retire once the building opens. It stays online, synced to the physical plant via edge computing.

Companies like Caterpillar use this setup as a “digital nervous system.” Edge devices process billions of data points in milliseconds. If a conveyor belt motor shows vibration patterns consistent with failure, the twin detects it immediately. It doesn’t just ping a human; it can autonomously reroute production to a backup line, maintaining throughput while scheduling maintenance.

This capability is vital for the “Gigawatt-scale” AI factories currently under construction. The power and cooling requirements for training large language models are too precise for manual balancing. The digital twin continuously weighs the cooling load against server output, optimizing energy efficiency in real-time to prevent grid strain.

Summary

Digital twins have graduated. They are no longer experimental pilots; they are standard operating procedure. By moving the trial-and-error phase into the virtual realm, manufacturers have decoupled innovation from physical risk. As supply chains become increasingly integrated, the next phase is inevitable: linking individual factory twins into a global ecosystem to manage macroeconomic shifts in real-time.