June 8, 1978. Intel releases the 8086. It wasn’t designed to be a global standard; it was a placeholder—a stopgap product to fill a portfolio gap while engineers worked on a more ambitious project. It didn’t matter. That 16-bit chip inadvertently dictated the language of modern computing for the next half-century.

Longevity like this is an anomaly. In an industry where hardware becomes e-waste in five years, the x86 instruction set has survived five decades. How? Strict backward compatibility. A program written for that original 8086 can, theoretically, still run on the silicon sitting in your laptop right now. This refusal to break the past, combined with aggressive performance scaling, cemented Intel’s dominance and built the digital infrastructure of the global economy.

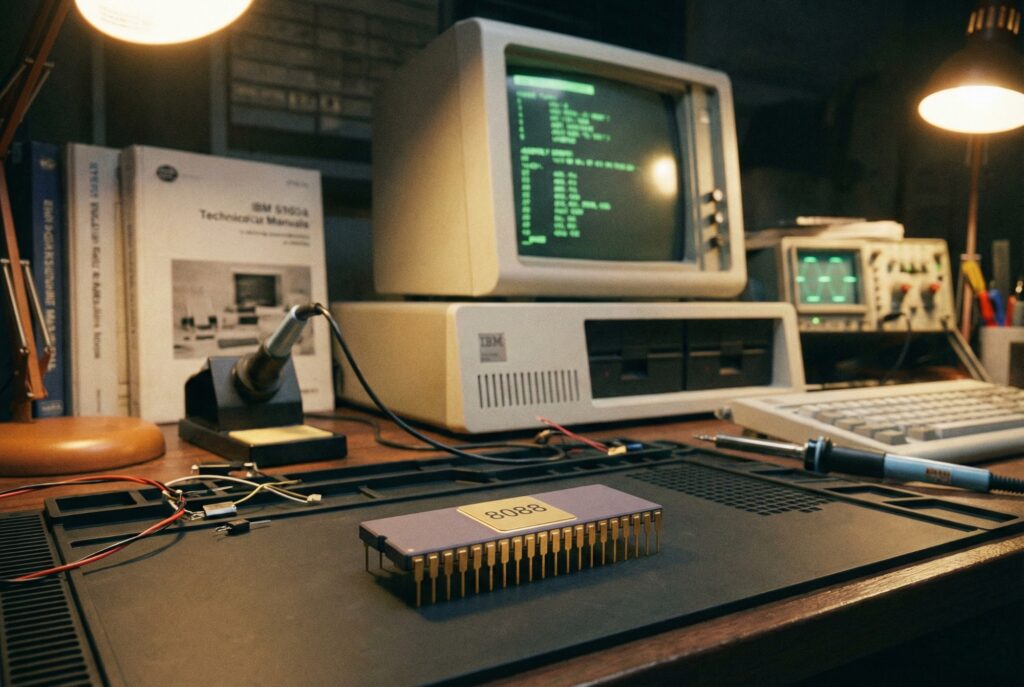

The Accident That Became a Standard

The x86 origin story isn’t about grand vision. It’s about practicality. In Santa Clara, Stephen Morse and his team engineered the 8086 to jump from 8-bit to 16-bit processing. It was a solid technical leap.

But the architecture didn’t win because it was the best. It won because IBM was cheap.

In 1981, IBM needed a chip for its first Personal Computer (PC). They bypassed the pure 8086 and chose its variant, the Intel 8088. The 8088 used an 8-bit external data bus, which meant IBM could use inexpensive, off-the-shelf motherboard components while still advertising 16-bit power.

That cost-cutting measure sparked a volume explosion. Because IBM used an open architecture, clone manufacturers like Compaq and Dell swarmed the market. They could build compatible machines, but they all needed the same engine. The x86 architecture went from a proprietary Intel product to the industry standard almost overnight.

The 32-Bit Revolution and the 386

By the mid-80s, 16-bit was cramping the industry’s style. Software was getting heavy; it needed more memory and better multitasking. Intel’s answer in 1985 was the 80386 (i386).

The i386 wasn’t just an upgrade. It was a foundational shift. It introduced 32-bit processing and “protected mode”—a critical feature for memory management. Before this, a single crashing application could take down the whole system. Protected mode built walls between programs.

This chip enabled the modern graphical OS, paving the way for Windows 3.1 and 95. It also marked a shift in strategy: Intel stopped licensing its designs to other manufacturers. If competitors like AMD wanted in, they would have to reverse-engineer the architecture from scratch.

Evolution of Specifications

The numbers below illustrate the sheer scale of Moore’s Law over five decades.

| Processor | Release Year | Transistor Count | Clock Speed | Architecture Width |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intel 8086 | 1978 | 29,000 | 5 MHz | 16-bit |

| Intel 80386 | 1985 | 275,000 | 12 – 40 MHz | 32-bit |

| Intel Pentium | 1993 | 3.1 million | 60 – 66 MHz | 32-bit |

| AMD Athlon 64 | 2003 | 105 million | 2.0 GHz | 64-bit |

| Intel Core i9-13900K | 2022 | ~25 billion | Up to 5.8 GHz | 64-bit |

The Clone Wars and the Pentium Era

The 90s belonged to the “Wintel” alliance, but the hardware monopoly was cracking. Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), originally just a second-source manufacturer for Intel, wanted a seat at the table.

Intel sued. They wanted to lock down the x86 rights. The courts disagreed. The ruling was nuanced: Intel owned the copyright on their specific microcode, but they couldn’t copyright the instruction set itself. That was enough. AMD used clean-room design techniques to produce functionally identical chips.

Intel fought back in 1993 with the Pentium. They dropped the numbers—you can’t trademark “586”—and focused on raw speed. This kicked off the “megahertz race.” For a decade, the only metric that seemed to matter was clock speed.

The 64-Bit Twist: AMD Takes the Lead

By the early 2000s, computers were hitting a ceiling. 32-bit memory addresses limited RAM to 4GB. That wasn’t enough for servers. Intel tried to solve this by killing x86. They launched Itanium (IA-64), a new architecture that wasn’t backward compatible. It required rewriting software or running it in a sluggish emulation mode.

The market hated it.

AMD took a smarter route. They kept the x86 foundation and simply extended it. They created “x86-64” (AMD64), allowing new chips to handle 64-bit memory while running older 32-bit apps at full speed.

Microsoft made the deciding vote: they would build Windows for AMD’s standard, not Itanium. Intel was cornered. In a rare moment of defeat, they had to license the 64-bit extension from their rival. Today, virtually every modern “Intel” processor is actually running on the architecture extension defined by AMD.

Multi-Core and the Efficiency Challenge

Then, we hit the thermal wall. Around 2005, engineers realized they couldn’t push clock speeds any higher without melting the silicon. The megahertz race was dead.

The industry pivoted to parallelism. Instead of one fast brain, why not two? Or four? The Intel Core 2 Duo and AMD Athlon 64 X2 launched the multi-core era. Performance gains no longer came from raw frequency; they came from software capable of splitting tasks across multiple units.

This sustained x86 for another decade, but it exposed a structural flaw: bloat. The x86 architecture carries 40 years of baggage. Every chip must include complex hardware to decode legacy instructions. That overhead burns power—a luxury you don’t have in mobile devices. This inefficiency opened the door for ARM, a streamlined architecture that now dominates the smartphone world.

The Future of the Instruction Set

As we look toward 2030, x86 faces a genuine existential threat. ARM-based silicon—like Apple’s M-series and Amazon’s Graviton—has proven you don’t need x86 compatibility to achieve high performance.

But don’t write the obituary yet. x86 is entrenched. It powers the servers that run the internet and the workstations that design the future. Intel and AMD are adapting, moving toward hybrid designs that mix high-power cores with efficient ones to blunt the ARM advantage.

The 8086 was a temporary fix that became permanent. While its monopoly on personal computing has fractured, the architecture remains the heavy lifter of the digital world. It survives not because it is the most efficient, but because the cost of replacing 50 years of software is simply too high.