Meta Platforms is overhauling the physical backbone of its artificial intelligence operations. On Monday, CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced “Meta Compute”—a centralized push to secure massive energy reserves and verticalize the company’s tech stack. The goal is ambitious: deploy tens of gigawatts of computing capacity by 2030. Long term, the company is aiming for hundreds.

The move marks a hard pivot. Meta is shifting from a social media giant that buys hardware to a vertical operator controlling everything from custom silicon to power plants. Leadership for the new division is split between Santosh Janardhan, head of global infrastructure, and Daniel Gross, a former AI entrepreneur. Janardhan keeps the technical keys—including the Meta Training and Inference Accelerator (MTIA) silicon program—while Gross handles supply chain strategy. Both report to Dina Powell McCormick, Meta’s new President, who is tasked with the political maneuvering required to finance these massive builds.

The Gigawatt-Scale Energy Strategy

Energy acquisition is the core of the plan. AI clusters consume power on the scale of small nations, forcing hyperscalers to abandon traditional utility grids. Zuckerberg’s target of “hundreds of gigawatts” makes current standards look like rounding errors; most large data center campuses today draw between 500 megawatts and one gigawatt.

To hit these numbers, Meta is betting on nuclear. The company recently finalized 20-year Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo. The deal aims to bring up to 6.6 gigawatts of new nuclear capacity online by the mid-2030s. This portfolio isn’t limited to standard plants—it heavily backs Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), a technology promising flexible deployment but lacking a long operational track record.

This strategy is a direct response to grid failure. The U.S. power infrastructure is strained, and interconnection queues can stall projects for years. By funding generation directly, Meta hopes to bypass the volatility of the public energy market entirely.

Restructuring for Vertical Integration

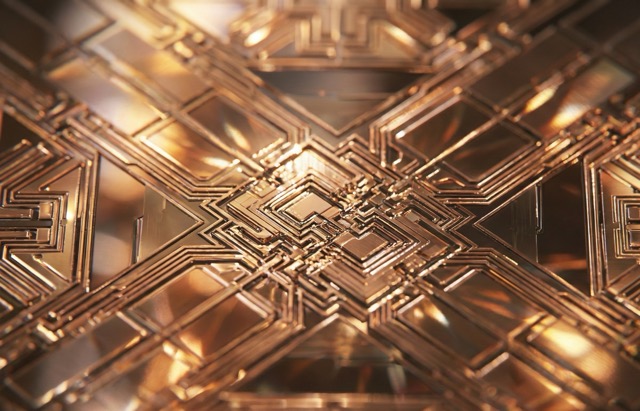

Structurally, Meta Compute is a cleanup operation. Network engineering, data center construction, and silicon design previously functioned as separate fiefdoms. Now, they are a single product unit. The logic is simple: tighter integration between custom MTIA chips and the physical buildings housing them.

The reorganization follows a rough 2025. Despite dumping a record $72 billion into capital expenditures, the “Llama 4” model landed with a thud compared to competitors. Analysts pointed to infrastructure bottlenecks that hampered training efficiency.

Meta is trying to stop that from happening again. By decoupling immediate execution (Janardhan) from long-term planning (Gross), the company wants to move faster. They are even experimenting with pre-fabricated “tent” structures for GPU clusters—facilities that can be erected in months, rather than the years required for concrete bunkers.

Competitive Landscape and Specifications

Meta is now on a collision course with Microsoft and OpenAI’s “Stargate” project. Both initiatives want to break the gigawatt barrier, but their methods differ. Microsoft leans on its OpenAI partnership and Azure’s existing footprint; Meta is building a self-reliant ecosystem for open weights and consumer agents.

The table below outlines the disparity between current standards and Meta’s projected scale:

| Feature | Standard Hyperscale Campus | OpenAI/Microsoft ‘Stargate’ (Est.) | Meta Compute Initiative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Target | 0.5 – 1.0 GW | ~5 GW (Phase 5) | Tens of GW (2030s) → Hundreds of GW |

| Primary Power Source | Grid / Mixed Renewables | Grid + Nuclear Ambitions | Nuclear (SMRs) + Grid |

| Key Hardware | NVIDIA H100/Blackwell | NVIDIA + Custom Azure Silicon | Custom MTIA + NVIDIA |

| Construction Timeline | 24–36 Months | 2028–2030 launch | Continuous (Rapid “Tent” Deployment) |

| CapEx Scale (2025) | ~$30–40 Billion | Part of ~$100B project | ~$72 Billion |

Financial and Environmental Implications

The price tag is staggering. Expect sustained capital expenditures topping $70 billion annually. This money doesn’t just buy chips—it builds roads, water systems, and electrical substations.

Then there is the environmental cost. Cooling data centers of this size requires millions of gallons of water. Meta has pledged to be “water positive” by 2030, but local opposition is growing in drought-prone regions. While nuclear power solves the carbon emission problem, it trades it for regulatory headaches regarding waste disposal and site safety.

Zuckerberg seems willing to absorb the risk. He frames the build-out not as a business option, but as a necessity for “personal superintelligence”—AI agents capable of complex reasoning for billions of users.

Industry Outlook

For top-tier AI developers, the era of “cloud rental” is over. Relying on third-party infrastructure simply doesn’t work when you need to train frontier models. The integration of power, silicon, and real estate suggests the new bottleneck for AI isn’t code. It’s physics.

If Meta Compute works, it establishes a private industrial base capable of training models orders of magnitude larger than Llama 4. But the execution risks are severe. SMRs are unproven at this scale, and regulatory scrutiny is tightening. Meta’s ability to deliver on these gigawatt promises will decide if they lead the generative AI race or end up sitting on a pile of expensive, stranded assets.